I don’t know about you and your

work habits, but there are times when I personally become totally absorbed in my

work.

The upcoming deadline, publication, or event fills my attention and,

while on the clock, all I can think about is finishing the task at hand and

preparing for the next project. And yet on other occasions I am preoccupied

with what I’ll be doing next weekend. How many hours until I can do as I

please? We alternate between spending all our time working and passing the

hours idly entertaining ourselves. The perpetual recurrence of Monday

always seems an insurmountable obstacle while the indubitable return of Friday

appears to us to be a liberation from the drudgery of our endless toil.

We live in an age consumed with

consumption and overworked with working overtime.

Is everybody really just

“working for the weekend”? When we are “takin’ care of business,” are we

actually overwhelmed by busyness? Do our “restful vacations” become restive

evacuations, bringing even more activity into our hectic lives?

Does man realize the deepest

meaning of his life only through labor?

To

consider these points I think it would be helpful to bring in the thought of

another German philosopher of the 20th century, similar to Hildebrand for his

passion for culture, his intellectual dedication to ethics, and his personal

commitment to standing up for truth: Josef Pieper (1904-1997). In his work Leisure:

the Basis of Culture, Pieper takes up this question central to the life of

man: is man made for work?

Does man realize the deepest meaning of his life

only through labor? If we do work in order to have leisure, how should this

downtime be characterized?

Certainly work is highly

significant to man in that through work man applies his energies to some

creative task, achieving a meaningful goal. Usually one earns a livelihood

through some form of labor, providing for oneself and one’s loved ones. There

is a rightful sense of accomplishment that one feels because one has done this

work themselves. They deserve the fruits of their labor.

On the

other hand one might be tempted to believe that one’s whole worth as a person

is dependent on how much they work.

Thus, consider a man who normally is the

main provider for his family. Unfortunately, he is injured in a car accident

and can no longer work. His wife, who previously only had a part time job,

switches to full time until her husband can recover. Before, both the husband

and the wife actively gave and received, albeit in different ways and to

different extents. Is the husband worth any less as a person because he is

unable to work? Did the wife have less value before she worked full time?

In accord with Pieper’s analysis, while hard work is rewarding and helps us to realize our capacity to create, an appreciation for the active dimension that work contributes in human life and culture must be balanced with an adequate consideration of the role that a more receptive attitude must play. The dignity and value of the husband and wife are not reducible to how much they work, though being able to provide for one’s family is a significant responsibility. Every human person is intrinsically valuable, having a dignity based on the very fact of their personhood. Though some might want to understand the value of a society as arising from the kind of work that it does, it is important to note the central role that leisure plays in culture.

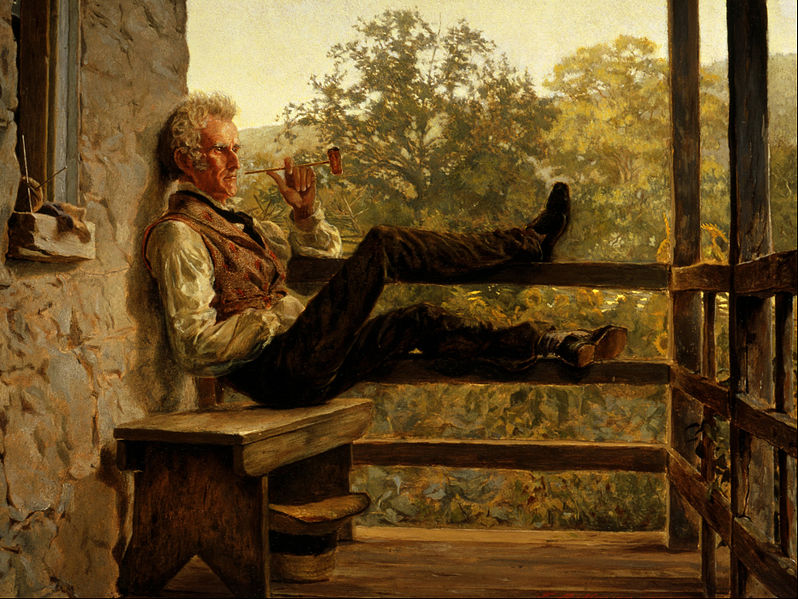

We must take time to consider the

beauty hidden in everyday life.

Pieper, following after Aristotle

(1), wants to say that a vibrant culture can only grow in the context of leisure.

Here leisure is not to be understood as equivalent with mindless entertainment such

as continuously watching television or self-indulgent vice like drinking to

excess. Rather, Pieper characterizes leisure as “a receptive attitude of mind,

a contemplative attitude.” (2) Relaxing from our constant drive to produce, to

build, and to work, we must take time to really look at the

world, to consider the beauty hidden in everyday life and to savor the truth

which we learn. In short, we must be contemplative. When we engage in this

attitude, we are enabled to receive the full meaning of creation and all its

many wonders. For many of the most profound dimensions of reality only disclose

themselves to the one who is willing to wait upon their revelation.

Thus, on a

Sunday afternoon, a peaceful stroll through the park is worthwhile without

accomplishing any work, even without a set destination. On one level, you are

resting from the tiring work of the week so that you may engage fully recharged

on Monday. Yet if this were the only reason you went on a walk, it would

turn out to be a rather dull walk. You would miss out on the beauty of the day.

The desire for rest might motivate your walk to begin with, but if your

thoughts were consumed with the work to be done on Monday, it would no longer

be leisurely. You only might experience it as a “recharge”: appropriate for

batteries but hardly for people.

When we engage in recollection,

we are able to return to our work with minds made new.

This

resonates with Hildebrand’s writing on “Recollection and Contemplation” (3) in

which he tells of the need for the human being to have time of restful

receptivity to the meaning of life and the world. (4) Realizing who we are

and who we are meant to be, we are enabled to lead our lives more fully in

accord with the truth of our being. When we engage in recollection, that

“awakening to the essential,” (5) we are able to return to our work with minds

made new, following after the purpose of our lives.

With a recollected mind we will

be able to take up our work not as an oppressive burden, but as a natural step

toward the time of restful celebration and festivity. True leisure, properly

enjoyed, gives us a serene peace that permeates the whole week and makes work

light. The joyful repose of Sunday can then open to work undertaken confidently

and calmly on Monday.

With a recollected mind we will

be able to take up our work not as an oppressive burden, but as a natural step

toward the time of restful celebration and festivity. True leisure, properly

enjoyed, gives us a serene peace that permeates the whole week and makes work

light. The joyful repose of Sunday can then open to work undertaken confidently

and calmly on Monday.

What do we need to change in our

week in order to make room for real leisure?

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1. “We are unleisurely in order

to have leisure.” - Aristotle Cf. Josef Pieper, Leisure, the Basis of Culture

(San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2009) 20.

2. Pieper, Leisure, 46-47:

“...it is not only the occasion but also the capacity for steeping oneself in

the whole of creation.”

3. Dietrich von Hildebrand, “Recollection and Contemplation” in Transformation in Christ (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2001).

3. Dietrich von Hildebrand, “Recollection and Contemplation” in Transformation in Christ (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2001).

4. Cf.

“Recollection and Contemplation,” 133: “The primary attitude of man, as a

creature, is a receptive one.” Also, cf. p.119: “contemplation represents a

specifically restful attitude, in which we...actualize our entire being.”

5. Cf. “Recollection and Contemplation,” 106: “Recollection proper always means an awakening to the essential, a recourse to the absolute which never ceases to be all-important and in whose light alone everything else discloses its true meaning.”

5. Cf. “Recollection and Contemplation,” 106: “Recollection proper always means an awakening to the essential, a recourse to the absolute which never ceases to be all-important and in whose light alone everything else discloses its true meaning.”

1 comments

Great article. Pieper always fascinates, and uplifts. To have rest, we need order. It reminds me of Horvat's work Return to Order where he coins the term "frenetic intemperance," which lies at the root of our frenzied economy and lifestyle.

ReplyDeleteNote: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.